RECENT anniversaries June 6 D Day 1944 and June 7, United Irishmen rise in county Antrim, 1798, are a very interesting juxtaposition of dates in terms of Irish freedom and worth a moment to reflect on.

Looking at both, so unlinked in historical context, yet so proximate calendar wise, the problems facing the stunted unfinished business of building an inclusive Irish national identity present themselves, hidden in plain sight.

The fight for Irish freedom is commonly reduced to a series of Catholic rebellions kicked off by a Catholic and Presbyterian one, that took place in 1798.

This period, complete with Church of Ireland martyrs Wolf Tone and Robert Emmet, has been viewed through a highly coloured lens by the nationalists and republicans who came later.

Irish freedom is far more complex a matter than the narrative of entitled nationally sovereign reconquest, resonating with emotive populism and the cult of martyrdom.

D Day was a battle fought in WW2, one of the few morally unambiguous conflicts in history.

In most conflicts there are rights and wrongs on both sides.

Not Nazism, Nazism needed to be eradicated.

While the Republic of Ireland remained neutral, tens of thousands of people, mostly men, from all parts of Ireland, fought in the British army in the great war against European Fascism.

The UK, with other powers, won this conflict and this contributed hugely and directly to Irish freedom.

That is a no-brainer to all but an ardent NAZI.

For what is the point of all this internal Irish terrorism, freedom fighting, what ever name it goes by, if you wake up one morning to Hitler’s vision for Europe?

Slavery and extermination as state policy, individual rights, even for the so called ‘Herrenvolk’ crushed.

To put all the freedom eggs in such a small basket as 1798 and subsequent rebellions and/or bouts of terrorism, is short sighted.

The tradition of Plunket, Pearse and Tone delivers a very partial freedom and not even for everyone.

Bobby Sands did not die for my freedom, Patrick Pearse did not die for my freedom.

Wolf Tone had a unifying idea, but republicans who came after, partly through their own doing, partially through the intransigence of unionists, have strayed.

There will be a united Ireland in a few years time.

Central to reconciliation rhetoric is the concept of the “shared island”.

The reality of this so called “shared island” is that the role of the UK in helping safeguard Irish freedom, outside of unionist areas, is not and cannot be celebrated.

Republicans would laugh down the road the idea that the British army had any role in Irish freedom and the rest of nationalism would hurry along behind them.

Nationalism needs to lift the hood on Irish freedom.

Not the least part of Irish freedom is the freedom to move on from a terrible past.

The role of people from the island in the British army helping secure Irish Freedom needs not only to be marked, but more importantly, normalised.

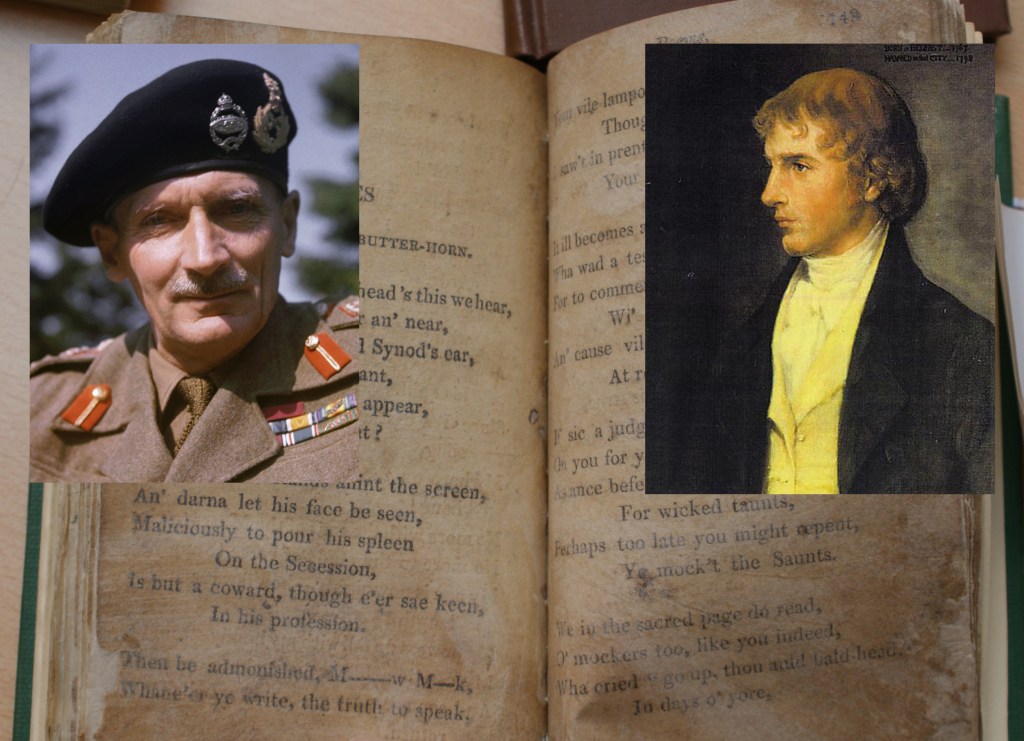

Paddy Mayne needs to take his place with Paddy Pearse, Bernard Montgomery with Henry Joy McCracken.

Not only as as part of the narrative of inclusion of the one million British people on the island, but as an acknowledgement of the multi faceted nature of Irish freedom, part of which is secured collectively with neighbours and allies.

When placed in that context I would certainly have no problem acknowledging the importance and role of the traditional ‘Irish Freedom’ narrative.

We want a genuinely shared island not the superficial counterfeit so commonly peddled by so many.

Leave a comment